Consider the Canon. Jane Austen is frequently thin on details and does not offer much data about the Regency’s social environment. She rarely addresses the great questions of the day, except for suggesting that Tom Bertram’s time in the West Indies left him scarred and damaged.

The same holds for settings. She does not expend great energy describing the bucolic life around Longbourn or Pemberley. Austen gives enough description to allow her readers to understand that Longbourn was not the grandest house in the area. At the same time, Pemberley was thought by many (especially Caroline Bingley) to be one of the greatest in all the land. Beyond that, she needn’t go as her readers—after all, she was writing for the 10% of the population who could read—intimately knew the world about which she wrote.

Austen also tends to shorthand many of her characters, giving them one specific trait that explains what readers should think of them. She counted on the fact that, just as she drew from her life, her readers knew people like Sir Walter Elliot, Mr. Woodhouse, Caroline Bingley, or William Collins. She gave them enough for readers to go “Oh, yes...”

On the other hand, Austen makes a particular effort to offer her readers enough data and information to explain why her characters acted as they did. We can recite by rote Darcy’s behavioral construct and what drove him to act in general and in specific. The same would hold for Elizabeth Bennet and Anne Elliot. Consider Elinor Dashwood, who, as the eldest daughter, had to act as the serious, sedate helpmate for her much put-upon mother, a woman both grief-stricken and financially prostrate. Would Marianne ever have been allowed to engage in her romantic fantasies if Elinor had not been the rock upon which the family was built?

Modern Austenesque authors seeking to create work that is not simply time-worn tales told against the same well-understood background are faced with a problem writers in other genres have had to address. They must offer stories driven not only by plot and character, but they also must create entire worlds in which their characters and the actions of the same can logically exist.

Authors like O’Brien, Woolf, and Parker, in addition to Austen and Gaskell, created original and compelling stories populated by interesting characters. They also imbued the plots and the characters moving through them with lifeforces that rise from a unique weltanschauung—a world view.

One of my favorite articles exploring the human mind is Sigmund Freud’s 1918 essay, “Civilization und Die Weltanschauung.” In this treatise, he examined various governing worldviews. Think of a Weltanschauung as the software a human mind uses to process information from the surrounding world. He was not the first to use the term. He had been preceded by Spinoza and Schweitzer, each of whom explored the nature of human thought.

Those techniques which humans use to adjust, filter, and construct their worldviews are, according to Freud, Religion, Philosophy, and Science. Whichever methodology used, the purpose of building such a lens was, according to Freud “[to give] a unified solution of all the problems of our existence in virtue of a comprehensive hypothesis, a construction, therefore, in which no question is left open and in which everything in which we are interested finds a place.” Simply put, a weltanschauung makes the world relevant and, thus, believable.

As should our Austenesque stories.

Each environment with which my characters must interact has to be relatable, whether in the Regency or World War II. How many InspiredByAusten readers fully understand the forces driving not only Regency Britain but also the other players on the world stage at the time…Russia, Prussia, France, and the United States? Why do those nations matter?

Because what went on even at the county level in Regency Britain was influenced by greater national interests. An example from one of my earlier books may be helpful.

In The Keeper: Mary Bennet’s Extraordinary Journey, a cataclysmic fire begins in a textile mill on the Mimram River in Meryton. The mill and half the town are destroyed, and dozens die.

Yet, suddenly, two militia regiments are dispatched to Meryton to assist in the rebuilding. Yet, I also needed to have the “new” Mary skinning a particularly noxious militia officer to provide an example for Maria Lucas while showing Georgiana Darcy a new side of her personality. But, I digress. See the passage from about four weeks after the fire was extinguished:

True to the promises made to Mr. Darcy, the Government had sent two regiments of militia to provide security and labor as rebuilding began. Mary was astonished to observe that the site of Watson’s factory had been completely cleared and the skeleton of a new facility was already taking shape with an army of red-coated and buff-jerseyed ants manhandling timbers and stone. Textile mills were a vital national resource needed to clothe the Peninsular Army and catch the wind for the Navy.

Another example—one of my favorites from Pride and Prejudice—adds context to a core plot mover in the book. The appearance of the militia in Meryton illuminates Mrs. Bennet’s and Lydia’s personalities specifically. It also introduces George Wickham into the mix and puts him and Darcy into immediate proximity.

Perfect…for the plot.

Now, why was the militia in Meryton? Why did the townspeople put up with a military unit walking about town? After all, soldiers were not the best examples of probity: drinking, gambling, carousing, and fighting were their norm. True, the enlisted men were usually confined to camp or under a sergeant’s jaundiced eye. The officers had the freedom of the streets…and the drawing rooms.

Mrs. Bennet couldn’t be that fluff-brained? We authors do have a lot of fun playing with her mean intelligence. But even the simplest of simple minds still could be skeptical of strange men, especially if she had five daughters in an era where the whiff of compromise destroyed a family’s reputation.

Here’s something Austen did not tell you—again, because her readers would already know this. The militia came to Meryton because there was no police force to control what the four-and-twenty families and the merchants feared: wanderers displaced from the land by the ton’s Enclosure Acts and poorly-paid and ill-fed factory workers. The gentry were thrilled to accept the militia's presence to insulate them from the threat of revolution. They had the salutary example of France’s Reign of Terror as a current event.

How little they learned from the loss of the Thirteen Colonies in 1783, who found the Quartering Act a bridge way too far!

That bit of context does not influence the story. It does, however, help me comprehend why Mrs. Bennet—and through her influence, Kitty and Lydia—easily conferred her approbation onto impoverished officers like Wickham. These men protected them from the Mob, much as the Penninsular Army protected Britain from Napoleon. They were exemplars—especially the officers—of what was good and safe.

As I build the stories, I have to sit back and understand the characters’ motivations and the invisible forces acting upon them. That means that I need to utilize my weltanschauung to create believable worlds for readers and listeners to employ their weltanschauungs to understand, appreciate, and ultimately enjoy my stories and characters.

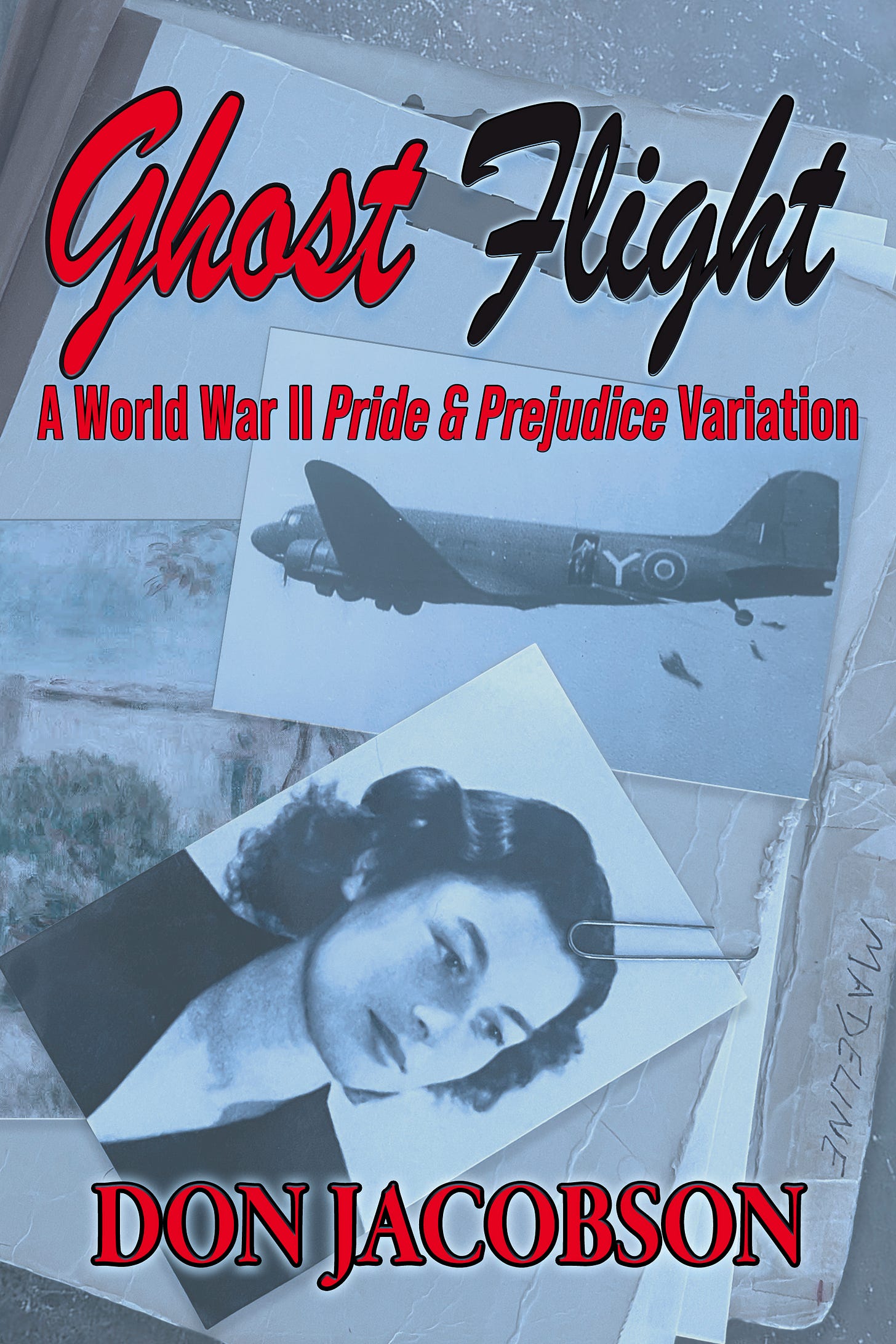

Please enjoy this excerpt from my latest book, Ghost Flight: A World War II Pride and Prejudice Variation. Note that I use the Freud article.

&&&&

My latest novel, Ghost Flight: A World War II Pride and Prejudice Variation went live on June 30, 2025. This 115,000-word book examines how Darcy and Elizabeth would have done their bit alongside millions of others from 1939 to 1945.

EmlynMara on FanFiction says of Ghost Flight:

Having cut my teeth on Helen MacInnis novels, this time period has always seemed very real to me, as have the lives and times of those who worked behind the scenes to aid the cause. This story is reminiscent of classic books by authors such as Leon Uris, Tom Clancy, Herman Wouk, Ken Follett, Alistair MacLean, and John le Carré. Well done.

Darkness Dims the Dawn

War’s clouds have choked the world for five years. Now, the Allies ready their great push to drive Hitler back to Berlin.

WAAF Section Officer Elizabeth Bennet and RAF Wing Commander Fitzwilliam Darcy have already done their bit. Both bear scars—seen and unseen—from their service. They have done much; now they will do more.

Elizabeth and Darcy step forward to undertake the deadliest of tasks: gathering intelligence behind German lines. They go knowing that the Gestapo’s destiny for captured Special Operations Executive agents was simple: a bullet.

World War II’s road to romance was bumpy. Cultivating affection’s fragile bloom while looking over their shoulders, Darcy and Elizabeth discover what is universal: the most ardent of loves.

Explore the dark, gritty world of Occupied France in 1944 at the shoulders of Fitzwilliam Darcy, SOE Agent Jeeves, and his radio operator, Elizabeth Bennet, Agent Madeline. This is a full-length novel of 115,000 words that asks how Darcy and Elizabeth might have served if they had been part of the Greatest Generation.

&&&&

WAAF Section Officer Elizabeth Bennet has been summoned to London after she reported that Wing Commander Darcy insisted that a message be delivered to “Preacher” before Darcy’s Dakota crashed in October 1943. She meets with a mysterious officer at 64 Baker Street, Room 306.

This excerpt is ©2025 by Donald P. Jacobson. Reproduction is prohibited. Published in the United States of America.

&&&&

Chapter Two

The radiator gurgled in its futile attempts to cut the winter chill. The sole window needed a thorough cleaning, as it had been unwashed since 1939. Opened blackout curtains—dusty and tatty—let Midday’s feeble light brighten the room. Crosshatched with tape, the hazed glass allowed only a feeble winter glow into the room. Green paint, unrenewed since Edwardian times, was dingy with the smoke of a thousand cigars and cigarettes. Worn linoleum and utilitarian metal furniture completed the picture. All contributed to a dog-eared air of weariness that bore down on late-1943 Britain, settling its heavy cloak around the uniformed pair.

The colonel’s eyes sagged at their corners as he stared at her. This unusual cast in a young man’s face told Elizabeth of too many interviews that had sent too many off into the maw of the machine that ground them up, fuel for its insatiable appetite. He was weary.

He absentmindedly pulled a pipe and tobacco pouch out from his pocket. His eyes never left Elizabeth as his fingers performed their actions by rote: stuffing, tamping, and, finally, lighting. Next, he fished out a pen and carefully laid it on the desk, stroking the barrel as if drawing strength from the inanimate case.

Through it all, he cataloged Elizabeth.

Grunting, the officer pursed his lips around the pipe stem. He flipped open the second folder. While she was adept at reading upside down and backward, all she could divine through the smoke cloud was her card-sized WAAF intake portrait clipped to a stack of papers. The colonel quickly unclipped the packet and casually flipped her photograph face down. Elizabeth shivered at his casual disappearance of her person.

“You like to climb trees.”

Elizabeth felt the need to clarify, although he spoke as a declaration. “Not recently, I should hope: my mother despaired of me and called me a tomboy. My older sister...”

“That would be Jane.”

A sleight of hand brought a deck of photos from the folder to the table. He spread them across the tabletop, card sharp-like. This, though, was no effort to impress.

Jane’s picture was front and center, pushed forward, his forefinger tapping the image, encouraging Elizabeth to expand. “Yes, Jane. Jane was the young lady every country mama could love. Our mother groomed her to sit atop the social pyramid, even if only in our corner of the county. My sister is sweet and demure, always sees the best in everyone. She doesn’t have a suspicious bone in her body.

“My father took a greater hand in my education and encouraged me to turn over stones to see what lay beneath. Sometimes that meant climbing trees.”

“Yet your sister joined up when the WAAFs became a going concern. She’s now a Flight Officer on Tedder’s staff at SHAEF.”[i]

“I said my father took a greater hand in my education. I did not say he ignored Jane entirely. She is just as motivated to serve our country as me. The WAAF was Jane’s tree, her escape from the gilded cage.

“Please do not mistake her calm manner for placidity. Velvet and satin will lead you astray. Jane is difficult to judge because she is always on guard. In her element, Jane is the exemplar, always on task and always correct in every stitch.”

He dismissed further exploration of Elizabeth’s dear Jane and nudged her picture aside. “Miss Jane Bennet found her place in Tedder’s suite. We could not use her in our business.”

Elizabeth felt the discussion moving on. Unsure he judged her kin lacking, she offered what she hoped would put a tick on her ledger’s plus side. “My next two younger sisters, Mary and Kate, have gravitated to nursing.”

A tarot reader could not have been more attentive in studying another two photos.

“Yaas,” he drawled, “Sister Mary Bennet has enlisted in Princess Mary’s Royal Air Force Nursing Service—too much of a mouthful, and the acronym is nothing but letter salad. She’ll see service as a flying nurse once the balloon goes up.”

He bore in. His baritone betrayed little. Elizabeth, though, heard a tone that suggested a closer experience with Mary’s daily portion. “Catherine is too young to enlist but volunteers at a convalescent home near your family digs in bucolic Hertfordshire.

“Netherfield is where we send men—boys, really—who have just survived Jerry’s worst. Most are burn victims—usually RAF bods—after they’ve had all the surgeries they can bear.

“I marvel at what the human body can take. Aluminum, while light, is as hard as a Damascus blade when cutting and crushing flesh. Petrol fires are pernicious. The scars are hideous. How these men get past their terrible disfigurement is beyond me.”

Elizabeth’s courage rose in the face of this transparent effort to discomfit her. She gave the colonel a correction, not a set-down. “Although she is only seventeen, my sister has an old soul. Kitty treats these heroes with respect and dignity; no matter her feelings, she never forgets there is a man inside. She has told me repeatedly that they may be different in appearance, but their sensibilities have not changed.”

“Hmmm. Based on what we learned, Your Miss Kate has shed her adolescent inclination to hide behind the youngest. Your parents must be comforted that Lydia remains unsullied by the war.” He frowned as he read a paragraph in the dossier. “Although, perhaps not for long.”

He paused and then ended her family assessment.

Silence descended.

Then he launched at her again. “Just as you are the opposite of your elder sister in appearance, are you likewise the flip side of her emotional coin? Are you skeptical of first impressions? Or do you make snap judgments?”

Elizabeth took her time answering this while she conducted a personal inventory. “When I was younger, I was prone to form opinions quickly without consideration. This was a harmless and youthful folly...usually. I either liked or disliked someone based on my prejudices. Yet, whether I enjoyed my breakfast or had swallowed some bone hidden in my sausage may have colored my judgments.

“After one unfortunate incident where I set my face against a young man who had unwittingly insulted me, my father took me to task and reminded me that my Weltanschauung trapped me. He dropped Doctor Freud’s article in my lap and sent me upstairs to read it.”[ii]

“In German?”

Elizabeth raised a haughty eyebrow. “Of course, Colonel: even the best translation loses something. For instance, if removed from its Teutonic framework, the jaw-breaking word Weltanschauung becomes the colorless and flavorless worldview. Now, if I may...?”

His sharp nod pushed her onward. “Once I took the time to think, to stop and look closely at myself, I quickly realized that my failing was that I believed what I perceived determined what was true. How did Lucretius put it? ‘That which to some is food, to others is rank poison.’ Fair or foul depends on your perspective. I was grandiose and infantile in thinking that the world revolved around me.

“I thought he was slighting me, my appearance. But to him, his poorly framed words were an effort to dissuade another from hectoring him to be more sociable. I did not willfully misunderstand him, but I took what he said as unvarnished truth, which demonstrated deficiencies in his character.

“That I later listened to gossip confirming my worst inclinations was and is a blot in my copybook.”

Grunting was this colonel’s favorite pastime. “Humph: sounds like someone I know. He insists that his is the only valid point of view, and evidence be damned! Those of casual acquaintance see him as a man of an officious nature bordering on insufferable arrogance. His family knows better, of course, that some of his behavior comes from a need to control everything because he lost both parents when he was at an impressionable age.

“But he is not the subject of this interview. You are. Your travels down memory lane suggest that you think you've reformed. What changed you besides Socratic self-examination?”

Elizabeth’s chin firmed. “The war, colonel, the war made me grow up; it changed me.

“No longer am I the girl who blithely gambols about the countryside. Now, I carefully survey the ground upon which I stand to see if it’s sand or stone. I watch people and compare their actions and mannerisms with what I know. If what they do is new to me, I become extremely cautious, preferring they call attention to themselves while I do my best to vanish.”

“And that is why we summoned you.”

[i] Air Chief Marshal Arthur Tedder was Deputy Commander (D. Eisenhower’s deputy) of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) during the leadup to and after D-Day. His rank was the equivalent of a full general. Flight Officer Jane Bennet (the equivalent of an army captain) was nominally Tedder’s adjutant and ran his office.

[ii] Sigmund Freud, Civilization und die Weltanschauung (1918), where Freud posits a unifying worldview, a lens through which individuals perceive the events around them.