For a JAFF author, the plot is queen.

A simple statement reveals a fundamental truth about our genre. An author can comfortably use the geography supplied by Austen to offer stories to readers thoroughly familiar with the lay of the land or buildings.

Hundreds of stories have spoken of Pemberley glowing in the afternoon sun as seen from the overlook. More have examined Longbourn’s solid, if not spectacular, architecture. Then there is Oakham Mount. Rarely do authors write of the path winding from the track between Longbourn and Lucas Lodge to Lizzy’s favorite refuge. Austen only offered that Elizabeth enthusiastically wended her way through the countryside before finally ending up on the summit plateau. The road from Longbourn to Meryton is equally undescribed, except that it is a mile walk. We assume it is not rutted nor, though, is it paved. The Bennet daughters and Mr. Collins do use it several times. Revealing conversation flows above and over as the characters walk along.

But is it shaded—as I had Longbourn Lane gradually turning into a tree tunnel over a century in the Bennet Wardrobe as sentinel oaks grew in—or a road between stone walls and exposed to the weather?

Decor is less critical unless it contributes to revealing something more about a character. We accept that Mrs. Bennet’s spendthrift ways might lead her to overdecorate the parlor. By inference, we are led to believe that Caroline Bingley would let loose the dogs of interior design upon Netherfield Park. This may be an artifact of the infamous orange dress in the 1995 television series. Austen only refers to her as a lady of fashion, and the fashion of the day did find much to admire in Egypt and China. Such choices are triggers for those of us with modern sensibilities. Austen never directly refers to any gauche and bourgeois redecoration.

I recall a description of a table in Netherfield’s Mistress’s suite from Laraba Kendig’s Longbourn’s Son. The author, through Elizabeth, reported that the table’s frail nature, with spindly legs and a delicate surface, was decorative but served no other useful purpose, unable to support a single teacup. A more apt description of the person who had ordered the table for her room—Caroline Bingley—could not have been written.

Austen’s core drivers—pride and vanity, honor and goodness of heart, misunderstanding and growth—buoy new plots bringing Darcy and Elizabeth together while Wickham and Lady Catherine muddy the waters. The authors accept the environment in which the characters lived in the Regency and concentrate on the story.

&&&&

Austenesque authors use Jane Austen as a starting point. We accept the predominant character constructs and use many of Austen’s core events—the insult, balls, visits, and deception—within our different plots that step beyond the confines of ‘Boy is a prickly SOB and manages to insult girl who, despite every protestation that she is unlike any other Regency heroine, proceeds to take against him because of his insult about her looks.’ Going Austenesque allows authors to explore worlds unimagined by Jane Austen.

Could Maria Grace have written her dragon series if she had not decided to step outside the 1930s Heyer model of romance and the demands that Variations focus on Darcy and Elizabeth?

Could Barry Richman have examined disease and medical/genetic conditions as he did in Doubt Not Cousin and Follow the Drum?

Could Kathleen Cowley have undertaken to reposition Mary Bennet as a detective and spy and become the heroine of her own series, The Secret Life of Mary Bennet?

Austenesque Authors abandon the comfort of Jane Austen’s world—by comfort, I mean the understood context through which the characters move—for the need to describe convincing worlds. Since readers are unfamiliar with the stage we set our players on, we must explain why it matters. Here, Section Officer Elizabeth Bennet meets a man she came to know as Colonel Barraclough at SOE’s Baker Street offices.

The radiator gurgled in its futile attempts to cut the winter chill. The sole window needed a thorough cleaning, as it had been unwashed since 1939. Opened blackout curtains—dusty and tatty—let Midday’s feeble light brighten the room. Crosshatched with tape, the hazed glass allowed only a feeble winter glow into the room. Green paint, unrenewed since Edwardian times, was dingy with the smoke of a thousand cigars and cigarettes. Worn linoleum and utilitarian metal furniture completed the picture. All contributed to a dog-eared air of weariness that bore down on late-1943 Britain, settling its heavy cloak around the uniformed pair.

Ghost Flight, opening lines of Ch. Two

The paragraph positions the characters in the middle of World War II. We understand that the country has been on its back heel for years. Britons are soldiering on, but their steps are slow. The ton’s denizens do not languidly lounge through afternoon teas of the type found in a Regency Grosvenor Square sitting room. Many of those classes have been imprisoned or marginalized for fascist leanings. For those who remain, the rationing regime has created a nation of thin, sallow-faced survivors, willing to get on with it, knowing that the only way to go was through.

One of the fun parts of building an Austenesque story is the geographic research. Whether it is Napoleonic Malta, Expansion-era Cincinnati, or Regency Meryton, finding and placing the towns in which our characters live is an interesting exercise. Old travel guides (Baedecker’s) illuminate the land’s contours and the historical surroundings. Blogs and commentaries consider where the fictional Meryton may be located.

A note on that question before I close. Many speculate that Meryton may have been modeled on the town of Harpenden. I, on the other hand, lean more toward Welwyn. Both are in Stevenage’s proximity. Welwyn, though, does rest on the banks of the Mimram River, a twenty-mile stream that empties into the Lea. I needed a river within my stories as the small valley would have been important in Celtic times. That allowed me to imagine fortifications atop Oakham Mount, whose crest overlooked the river. Opposite Oakham rose the Chiltern Hills. Then Mr. Bennet could write his paper, Considerations on Pre-Celtic Inhabitation of the Mimram Valley (1806).

Darcy accepted her hand and clambered to his feet, doing more damage to his pantaloons, this time the knees. Once he turned back to face his lovely savior, his view was of Elizabeth facing west and looking across the valley toward the Chiltern Hills. A halo surrounded her. That vision split his life into one of the eternal opposites: before and after. He could not have loved her more than in that moment, although he would spend years trying.

In Westminster’s Halls, Ch. Sixty-two

Many of my books use geography to establish the emotions I want readers to experience.

Whether JAFF or Austenesque, when well-composed, both methods allow readers to immerse themselves in stories growing from the timeless tale.

&&&&

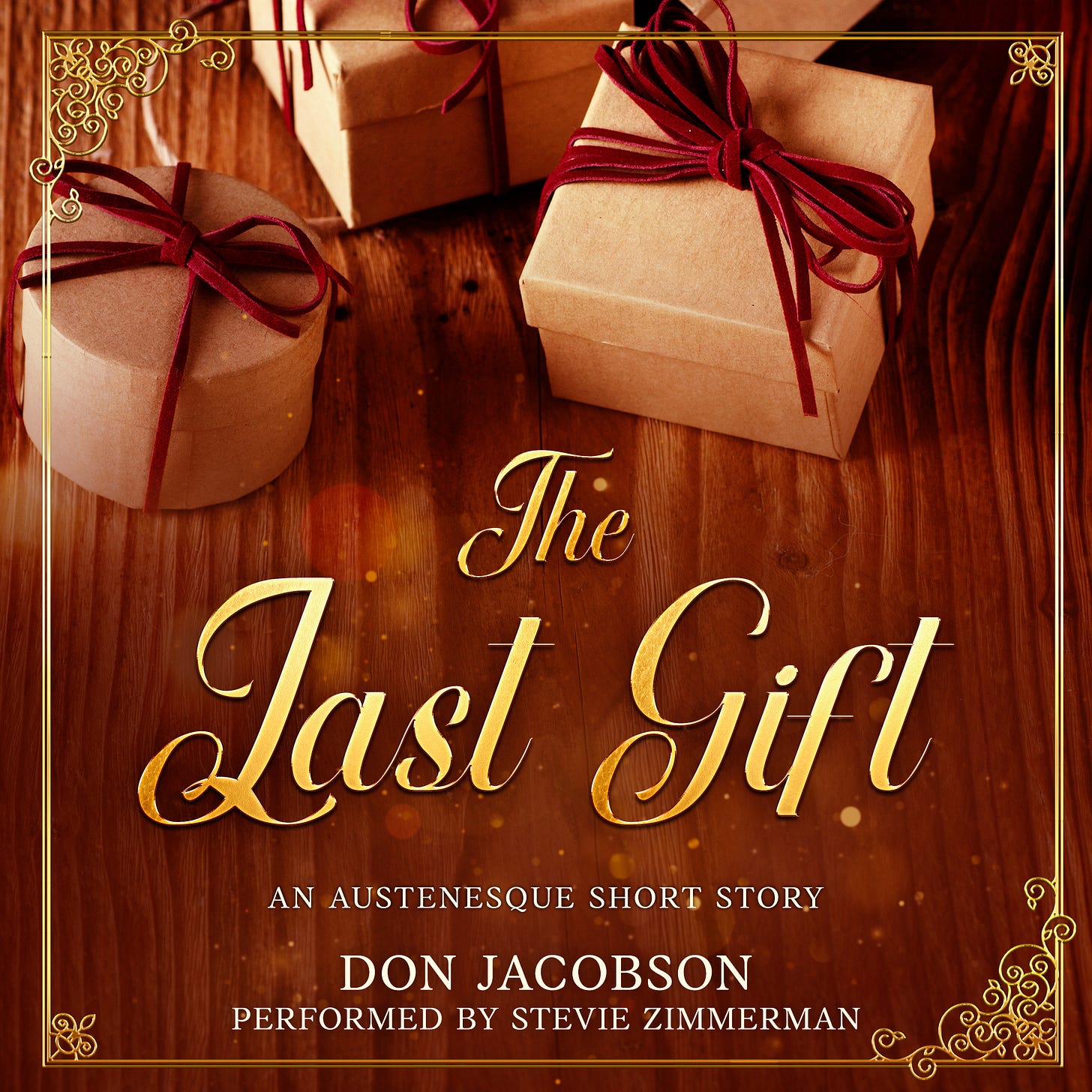

We are nearing the end of the Year of Jane Austen’s 250th Birthday. Many of you are familiar with my speculative short story, The Last Gift, in which I consider the premise that July 1817 was not the end but rather the beginning.

The Last Gift worldwide link https://mybook.to/A7Ayt4

The tale has been well-received. My favorite review comment comes from D. McMaster.

“I’m reminded of the opening of J.R.R. Tolkien’s saga, The Silmarillion, where the world and its inhabitants are sung into being; in Mr. Jacobson’s short tale, it is written into being.”

To be mentioned in the same sentence with J.R.R. Tolkien is an honor.

The story has been longlisted for the 2025 CIBA Sea Shorts award.

Stevie Zimmerman’s story performance is now available at Audible stores worldwide. This 30-minute “quick listen” is well worth it to enjoy one of the great performers specializing in our genre.

US Audible Link: https://www.audible.com/pd/The-Last-Gift-Audiobook/B0FVNXKRTP

The performance is available at Audible stores worldwide.

This excerpt of The Last Gift sets the stage for Jane’s interactions with Elizabeth and Elinor. The Last Gift is ©2025 by Donald P. Jacobson. Reproduction is prohibited.

&&&&&

The grass tickled her nose. A breeze rubbed her arms and legs. Birds twittered. The air carried a sharp freshness, reminding her of the fortnight surrounding her birthday. With that came a feeling she had stepped into the happy neighborhood she had known as a girl. Although southerly, Steventon still enjoyed a clime that allowed year-end snow to whiten the bushes and trees surrounding the rectory.

This dream—for was not this the safe place into which she slipped to escape her illness’s fell fingers?—pushed vividly against her. Jane was sure this was a last reverie—tendrils of its images wound through her consciousness. The air’s muted aroma was all that remained of her sister’s ministrations. Had they brought her to this instant? Ancient parishioners spoke of life flashing by in the moments before the spirit started its journey Home. Old crones, she had scoffed, telling tales to comfort themselves. To a youngster, such talk smacked of a wish to leap backward, spoken by people who saw the veil thinning.

Now, though, she yearned for this whatever-it-was to endure for more than a flash.

As her mind threw off the ailment’s wicked fingers, clarity shocked her.

Late autumn’s scent—dried leaves and fresh needles—pulled at her, demanding attention. The early morning breeze spoke of damp and dew hiding yesterday’s trodden tracks, leaving an unmarked meadow akin to a virgin quarto sheet anticipating her pen. The zephyr dragged its feet across her, molding garments to flesh, giving dimension, and erasing thoughts that her lot was to be that of a wandering wraith, invisible and untethered.

This vision is too concrete to be anything but life. ’Tis madness, for I was preparing to meet my Lord. Am I dead, or have I lost what few faculties my disease had ignored?

Contrary to human nature, I pray for the former. Descending into Bedlam’s realm at this late date would be a destiny I could not bear!

I am outdoors, in the country. Sound and smell add their touches of verity. If I am dead, why can I feel the ground beneath my back?

So, I return to my original question: have I taken leave of my body or my senses?

Jane opened her eyes and gazed into the boughs overhead. Was this the Norway spruce on the rectory’s East front, the tree Papa claimed inspired him to write bucolic homilies for his congregation?

What is this? I was in Winchester, not Steventon, last I recall. Now, I find myself reclining under the pruned arbor where I would sit for an afternoon, my commonplace book on my knee. Here was the first space where I found refuge to set down my juvenile scribblings.

And why do I lie on the ground when my bench rests a foot away?

Embarrassed, Jane scrambled to her feet unhindered by objecting knees, brushed off the tails of her redingote, and dropped onto the painted wooden seat. From this vantage point, more of the unusual expanse became clear.

A lawn that had never existed now carpeted a gentle slope outside her girlhood’s home before ending on a pond’s banks, large enough to be charitably termed a lake—if you squinted. She half expected to apprehend a fellow splashing about, his boots and topcoat on the shore. How would the transparent, damp chemise draped over a manly torso reveal unseen mysteries as he rose from the water? That, though, was a girlish fantasy about the male of the species. While a gentleman on his property might engage in such antics in private, he would never abandon propriety so entirely as to allow anyone to imagine him in such dishabille—much less see him.

On an estate she was, although whose and where?

Although she knew it to be impossible because her brother’s freehold was dreadfully far from Steventon, Jane sensed that Godmersham Park—mayhap Pemberley or Netherfield—rested behind the familiar rise to her left. If she walked along the path running up to the knob’s crest, she knew she would see a great house, smoke rising from its chimneys, nestled within lush fields. However, that situation had to be a bit of faerie dust clouding her sensibility.

Utterly inconceivable! Mayhap that is the rule in this place: that the most improbable becomes fact. I would wager a pound to a penny that Northanger Abbey and Mansfield Park lie below Oakham Mount’s overlook. Oh my! Oakham Mount is its name!

How curious: such a world, created by my nib, is now nearby!

The happy sounds of a kitchen hard at work drifted through an open window. Baking bread—or lemon bars—embraced Jane with its comforting aroma. In waking dreams that chased her to the writing table, she had imbued her heroines’ homes with the comfort and familiarity of Steventon Rectory or Chawton Cottage. Whether she called them Longbourn, Kellynch, or Hartfield, they were as familiar to Lizzy, Anne, or Emma as was her father’s parsonage to her, warm and safe: Home. Even Fanny’s aerie above Mansfield Park’s eaves gave her similar sanctuary, rarely breached by tormentors. There, Miss Price could retreat and mull over observations of her relatives’ behavior.

As for her years spent in Bath, Jane smiled about how she enjoyed observing the follies of those wandering the town’s byways. Being seen was far more important than acting sensibly. Their attitudes and dress—akin to Mr. Hogarth’s etchings—were the cloth she used to craft the caricatures familiar to her readers. If the characters’ siblings were less congenial than hers, that made for a better story.

Loved this post and the excerpt! I have that book on my Kindle and can't wait to read it!

Love this post and how authors write worlds into being. When I’m really immersed in a story the author has truly created a new world for me to experience.