“The most famous gap in Mansfield Park, however, is the “dead silence” that follows Fanny’s questions (p. 171) about the slave trade. Critics debate whether that silence would be filled by a condemnation or a defense of slavery, but surely the significance of the silence is that it could never be filled in a novel like this—and thus it registers all that the novel cannot accommodate.”[i]

As I edit the final version of In Westminster’s Halls, I have been thinking about how we can use Austen to understand social questions of her time and today.

In recent years, Austenesque authors have shifted their attention to how Jane Austen looked at the leading issues of her time. Of these, of course, was war and peace. The overarching existential threat posed by the French Emperor intruded into the lives of Britons from the very highest reaches of Mayfair to riverfront warrens like Seven Dials. The war was unquestionably the backdrop against which British life played out. The economy, taxes, food, and work were only a few of the modalities which the war influenced.

However, suppose writers focused only on how the war intruded into Fitzwilliam Darcy’s and Elizabeth Bennet’s lives. In that case, we would lose sight of the vibrant social questions considered significant by the middle and upper reaches of social thought. Of these, I have concluded the abolishment of slavery dominated.

Proponents of abolishment in the late Eighteenth Century had to contend with the war. Slave traders and owners persuasively argued that abolition would decimate the British sugar economy when its duties were most needed. These forces also pointed to the fact that Revolutionary France, despite its protestations of equality, had yet to end either the trade in human bodies or slavery itself. They conveniently ignored the fact that the United States Constitution included a clause that ended the American slave trade in 1807.

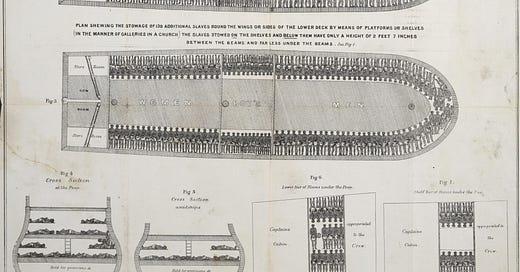

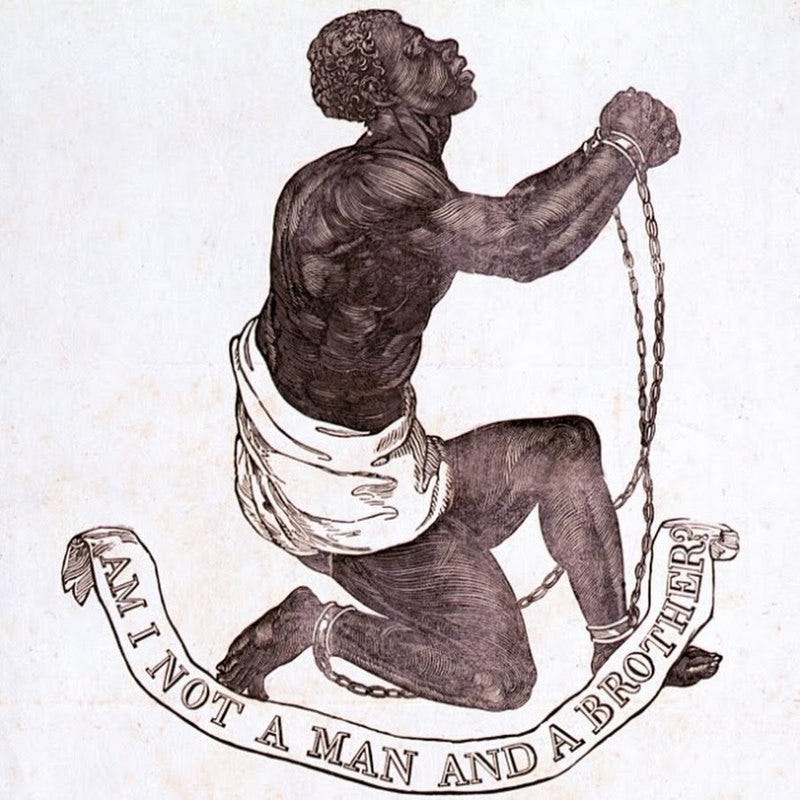

Thomas Clarkson was an establishment voice—a rector’s son and a deacon himself—who articulated the case against the ownership of other persons in his award-winning 1785 Cambridge Latin essay. His thoughts stirred sentiment against slavery. However, the politics of the time could not accept total abolition; the economic consequences were too frightening for those who had based their fortunes on Caribbean sugar.

A different tack was required. Clarkson and his allies, Wilberforce and Grenville, split the question, attacking the trade and intending to move on to overall abolition. Akin to the quote from Professor Claybaugh above, my novel cannot discuss the strategy from the defeat of the first attempt in 1793 to the victory in 1807.

However, the professor notes that Austen’s silence on slavery is vital: not because she either approved or disapproved but rather that, being an intentional writer, the Lady chose to say nothing when she had every opportunity to say something. Her readers would have noticed that. They also understood that Sir Thomas Bertram’s fortune in sugar rose from his Caribbean slave plantations, and, thus, even in its silence, Mansfield Park speaks about slavery.

Arizona State University’s Professor Devoney Looser has frequently written about Jane Austen and slavery. She looks past the Austen family’s connection to the institution—often misconstrued—in new readings of the Reverend George Austen’s role as a trustee of a friend’s marriage settlement, which included an Antiguan sugar plantation. Many commentators have used this to conclude that the family was pro-slavery.

However, how does Looser see Jane Austen’s thinking about slavery?

“Jane Austen directly addresses questions of slavery and the slave trade in two of her novels, ‘Mansfield Park’ and ‘Emma.’ She included a mixed-race West Indian heiress in her unfinished and long unpublished last novel, ‘Sanditon.’ In her private letters, she once wrote of loving the writings of Thomas Clarkson, a noted anti-slavery activist. This isn’t a lot to go on, but it shows that Austen was aware of and interested in questions of race and slavery,

“I believe the textual evidence points to her being an advocate for reform. This new evidence shows that her family’s affiliations to slavery and colonialism changed over time, from 1760 to 1840. During the period of that time when she was alive, 1775 to 1817, there were also immense changes afoot,” she added.[ii]

I agree with Professor Looser. Jane Austen was fully aware of her time’s great questions and was moved by them. In Westminster’s Halls embodies my thoughts about how Jane Austen might have addressed the ways activists ended the British slave trade. Into that ‘dead silence,’ I have poured a blend of Bennets, Darcys, Bingleys, Fitzwilliams, and characters from my other works.

In celebration of Summer Binge-Reading, I have put the Volume One e-book of the Bennet Wardrobe Series, The Keeper: Mary Bennet’s Extraordinary Journey, on sale for $2.99 or in local equivalent at all Amazon platforms worldwide. Offer Expires June 8, 2024.

Mary Bennets Extraordinary Journey

&&&&&

This excerpt of “In Westminster’s Halls” is ©2024 by Donald P. Jacobson. Reproduction is prohibited.

Prologue

Anne liceat invitos in servitutem dare?

(Is it lawful to make slaves of others against their will?)

Cambridge Latin essay topic, 1785

As it is usual to read these essays publicly in the senate-house soon after the prize is adjudged, I was called to Cambridge for this purpose. On returning however to London, the subject of it almost wholly engrossed my thoughts. I became at times very seriously affected while upon the road. I stopped my horse occasionally and dismounted and walked. I frequently tried to persuade myself in these intervals that the contents of my Essay could not be true. The more however I reflected upon them, the more I gave them credit. Coming in sight of Wades Mill in Hertfordshire, I sat down disconsolate on the turf by the roadside and held my horse. Here a thought came into my mind, that if the contents of the Essay were true, it was time some person should see these calamities to their end. This was in the summer of 1785.[iii]

***

The Road to London near Wades Mill, Hertfordshire

Tom Bennet removed his hat and turned his face to the sky. The summer sun warmed him and silenced the small voices that had beset him since yesterday in Cambridge.

Bennet rode toward Meryton this morning after spending a sennight at his alma mater. The call of the great university’s towers rang loud in the years after his time reading the classics. Longbourn held little attraction for Bennet, although, as his father’s heir, he understood the need to be an attentive understudy. Yet, his heart always leaned toward the bookshelves lining the study. Father and son had agreed that the racks were Tom’s province while Sam Bennet managed the estate’s affairs from the oak worktable in front of the window overlooking the gray and white river-pebbled front drive. A burgundy leather wingback chair and low footstool by the hearth allowed the son to disappear into Plutarch or Seneca while being near at hand in case the father had a question about a tenant or an expense.

A few days short of a fortnight had elapsed since his Ancients master had written Tom about the upcoming reading of the year’s winning essays, a new tradition now set at the end of Easter Term. He had urged Bennet’s attendance with an unusual appeal:

‘I have written young Bertram, but I doubt he will attend his old tutor. He may not be in the country if his father has sent him off to the family plantations in the Carib. The loathsome practice that fills the Bertram coffers—and not distance—may be why he would avoid the symposium. I may underestimate your friend by tarring him with the same brush as his father, but I may not.

‘That is why I take up my sword and beseech you to return to the crèche from which you sprang with such promise. I regret I could not reveal Aristophanes’s allure more convincingly and entice you to abandon your familial responsibilities. That is an old story, and I cannot belabor you with my disappointment: of such, many a life is made. You, my pupil, are not built for regrets.

‘Other riches may entice you to abandon grain husbandry and root vegetables briefly…

‘Our former master at Magdalene, Rev. Peckard, who is—as it turns out—a hidebound radical, was floated to the heavens last year as the university’s vice-chancellor. Safe in the sinecure, the old Oxonian abandoned his conformist stance and rattled our masters with the Latin Essay competition based on the abolishment question “Anne Liceat Invitos in Servitutem Dare?”[iv]

‘Whilst matriculating, you may have encountered Thomas Clarkson, the son of a Cambridgeshire cleric. He was a year behind you and, admittedly, not of our august Magdalene community. If you attend for no other reason—although I would be flattered that you would bless me with the opportunity to share a bowl of tobacco and a dram of Warre’s—you must for his lecture. With all the students having fled to England’s four corners, your old rooms await.’[v]

And, so, Bennet begged his father for a fortnight’s freedom. That worthy smiled in recollection of the busyness owned by a man with but twenty-five summers. There would be time enough to narrow his son’s horizons from the greater world to a small market town, limiting, although only twenty-four miles from the center of the world.

Now, the road to Hertfordshire found itself paved with questions that elbowed their way into Tom Bennet’s ken whether he wished it or not. Longbourn’s acres had remained unchanged for the past century since the India House trader Christopher Bennet had brought it under his control. Tradition dictated much of what the Bennets and their tenants undertook on the land nestled in the bend of the Mimram. The world rarely imposed upon Meryton.

Tom was pleased that colonial slavery had never taken root on the old island. Influenced by Edmund Burke, like his father, young Bennet fully embraced country-whiggish tendencies to despise those who made their bread from the broken backs of slave labor or through commerce in weeping souls. Aristocrats who tried to keep their hands clean by dealing through men of business while adding thousands from the sugar trade into their accounts likewise earned his scorn. His contempt for those so evil as to suggest the Bible sanctioned their acts made Bennet particularly receptive to the singular essay he had heard scarcely two days ago.[vi]

Clarkson, a St John’s graduate—Bennet did not eschew the other colleges—offered a thesis setting on its head every pro-slavery argument. Clarkson tore off the fig leaf and rent the veils to render impotent every claim made to give cover to any—owner, procurer, or trader—seeking to distance themselves from the pernicious vileness. Clarkson’s case resonated so profoundly that Bennet barely recalled leaving Cambridge in the dawn’s morning pink. He hardly noticed the road home to Longbourn. What he had heard set loose the dogs of doubt, mainly what he could accomplish as a gentleman of a modest estate. Over the miles, his study had become darker and more unsettling. The world about him faded the deeper his contemplations. His inattention had let Cato’s pace slow to a bare walk.

Bennet rode alongside the Mimram below Ware. The sound of Wades Mill’s great wheel was the backtone surrounding him. As he turned his face to the road ahead, a surprising tableau appeared: another man, a traveler Bennet supposed, sat on the verge, head supported by both hands. A hat obscured his face, but his clothing was gentle, if not first circle, quality. His horse cropped the tufty grass a few feet away. The subject of Bennet’s attention never moved, even when Cato approached and halted nearby in response to Bennet’s gentle tug. However, as he dismounted, the vagabond let loose a gust of a sigh, giving evidence of life.

The man lifted his head, wholly surprising Bennet to the extent that he would never forget their first encounter. The man who had left him so troubled sat on the ground before him: Thomas Clarkson.

“Ah, friend,” Clarkson began, “Are you an angel or a demon? Although I own you look like neither. However, I will be optimistic and pray that one of Gabriel’s minions has come to me as he did Moses in the desert. I fear I am in no state to wrestle. I have been doing more than enough of that as I try to return to town. The weight of my thoughts has become so great that I worry my poor bay could not carry me further.”

Bennet’s laugh at Clarkson’s dark humor shivered the afternoon air. “I must agree that you are the thinker of deep thoughts, but you cannot regret those ideas. You, sir, for I heard your talk, are on the edge of a great leap that will define our generation and, perhaps, those yet unborn. Would that I knew where you would lead, for I would account myself to be a follower.”

“Then you would be my first,” Clarkson ruefully said, “but maybe that is to both our fortunes. I may lead you to spend your life in a mad pursuit of the unattainable. One person—you—I could quickly turn away from my path. It will be exceedingly more difficult to dissuade a multitude. Perhaps I should seek my folly—as that is how our betters see it—in solitude.

“You see, sir, while I wrote the words, it was not until I read them aloud to men like you that they impressed upon me their integrity and, thus, their import.

“Now, when I close my eyes, I see the outlines of a great Cause…”

Bennet stepped in. “A great Cause: that has been roiling my spirit for a dozen miles. Ending the Egyptian Exile of millions and saving our collective souls seems a task that even Heracles would find beyond his demigod powers. What can I, the eldest son of country gentry, do? We have little reason to traffic with those who would hold others in bondage.”

Clarkson struck like an adder. “Do you put sugar in your tea?”

Bennet looked at his feet, ashamed. A gentle hand on his arm caused him to look up into a pair of warm brown eyes. “Do not be chagrined, dear sir. That was unkind to abuse one espousing my crusade.

“I, too, have a sweet tooth, much to my mother’s cook’s delight. My weakness is her lemon bars. I regret that I will have to forgo that treat until no man must brave the lash to sweeten my afternoon.”

He stuck out his hand. “Allow me to introduce myself to a fellow Cambridge man. Clarkson. Thomas Clarkson of Cambridgeshire, London, and, I imagine, anywhere that will have me.”

Bennet’s chuckle rumbled deep in his chest. “Bennet. Thomas Bennet of Longbourn near Meryton, but a few miles ahead down the river road leading to Hertford. You must call me Bennet, and if you allow the familiarity, I will call you Clarkson.

“You just said ‘anywhere that will have me.’ I can promise you that such a harbor rests below a knob atop which ancient fortifications brood. We call it a ‘mount,’ but it is just an orphaned shoulder of the Chiltern Uplift, split from the main ridge by this stream—the Mimram—digging its way to the Lea. Longbourn is but ten miles away. You, Clarkson, will find a berth there today and whenever you wish. I will not be gainsaid!

“Let us remount, for I cannot allow you to lay by the roadside when my parents’ parlor awaits—oh, and my father’s port. Perhaps we can agree that while the Portuguese have a checkered record in Brazil, Douro’s grapes are grown by free labor. That will be my father’s position, and I doubt if our youthful ardor will shift his taste to gin.”

Clarkson tipped his head back in hearty laughter. “Bennet, I swear I will allow the elder Bennet his fortified wine if he takes his tea with good, free English honey.”

They mounted and rode on little thinking that of such serendipitous encounters are lifelong friendships made.

[i] Amanda Claybaugh, Introduction to the Barnes & Noble edition of Mansfield Park by Jane Austen. (New York, 2004). P xxxii.

[ii] Devoney Looser interview with ASU News, “New Information Uncovered on Austen’s Family Ties to Slavery and Abolitionism,” undated electronic newsletter. https://news.asu.edu/20210614-regents-professor-devoney-looser-uncovers-new-information-jane-austen%E2%80%99s-family-ties-slavery

[iii] Clarkson, Thomas (1808) The History of the Rise, Progress, and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave-Trade by the British Parliament. Vol. 1. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees and Orme. pp. 209–210. Spelling and punctuation in context. Accessed from https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/10611.

[iv] For more on Reverend Peter Peckard (c. 1718-1797) see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_Peckard. The translation of the essay question is “Is it lawful to enslave the unconsenting?”

[v] Thomas Clarkson (28 March 1760 – 26 September 1846) was an English abolitionist, and a leading campaigner against the slave trade in the British Empire. He helped found the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade (also known as the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade) and helped achieve passage of the Slave Trade Act of 1807, which ended the British trade in slaves. Warre was a leading exporter of port wine from Portugal having begun under another name in 1670.

[vi] Edmund Burke (1729-1797) was an Anglo-Irish statesman and philosopher. He served in Parliament for twenty-eight years. According to Bourke (2015), “Burke was a proponent of underpinning virtues with manners in society and of the importance of religious institutions for the moral stability and good of the state.” This fits well with my impression of the conservative, but not Tory, values held by the Bennets.